Armenian Art and Architecture

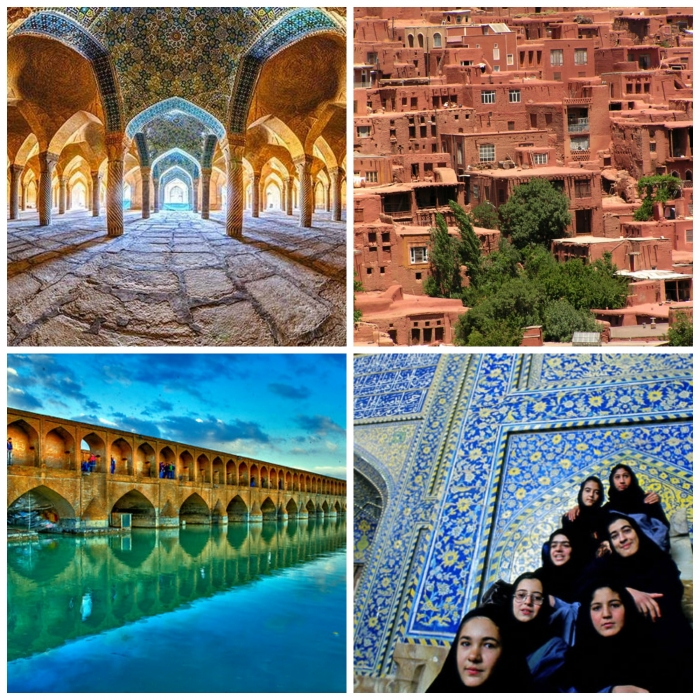

Architecture

In the realm of Armenian art, architecture takes pride of place. It was the first of the arts of Armenia to be seriously studied, and to this day Armenian architecture receives more scholarly attention than all of the other arts combined. The separateness of architecture from the other arts is not due just to size, though certainly the immense mass of any building compared to other works of art is so disproportionate that no real comparison is possible, nor to the labor, in the case of architecture perforce collective, required for its creation. Because buildings are natural vehicles for decoration, they differ from other art objects by often incorporating in themselves the two most important of the other arts: painting and sculpture.

In the study of architecture, however, primary attention is not given to the decoration, but to the structural forms of buildings and their evolution. Thus, monuments are analyzed by their architectural aspects -- the general design or look of the interior and exterior of buildings -- and architectonic considerations -- the methods used to construct them. Classes of buildings are studied by their plans. Everyone is familiar with certain common types of structures; their names immediately evoke specific images: skyscraper, lighthouse, pyramid, windmill, stadium, Greek temple. Other types of buildings are less precisely visualized, because their forms are diverse: houses and churches, for instance, vary greatly in different parts of the world. They are differentiated architectonically by materials and methods of construction, architecturally by their shape.

The form of a building is expressed by its ground plan. Simply stated, a ground plan, or just plan, is the contour of the walls of any structure with all of its entrances and other openings indicated in an overhead view of the building magically sliced away at ground level. The thickness of the dark black lines, the size of the empty spaces for doors, reflect accurately and to scale the actual size of walls and openings.

The history of Armenian architecture is in reality the history of the development of a single type of building: the church. Two observations should come to mind, each raising certain questions. First, since the church is a Christian building for worship, and since Armenia was converted as a national entity in the early fourth century, does that mean that there is no architecture in Armenia before Christianity? No. We know very sophisticated building techniques were in use in Armenia and a strong architectural tradition in stone was exercised for more than a thousand years before the first church was built.

Unfortunately, only a handful of pre-Christian examples has survived and they are from three distinct epochs: Urartian, Hellenistic, and late Roman. They will be discussed briefly in chronological order. A considerable number of temples and fortified garrison cities are known belonging to the kingdom of Urartu (ninth to the sixth centuries B.C.), the most famous examples being the garrisons of Erebuni and Karmir Blur in Armenia, Toprakkale, the royal capital near Van, and the temple of Mousasir (known from an Assyrian carving). None of these survived above ground; they were all discovered in the past century by archaeological excavations. The kingdom or Urartu itself was forgotten for 2500 years after its destruction in the early sixth century B.C. until it was literally dug up in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Urartian architecture used carefully cut stone often of very large size for the foundations of walls and the supports of wooden columns for temples and assembly rooms. The compact efficiency of such towns as Erebuni, the innovative design of the temple of Mousasir, and the remnants of simple houses with primitive domes points to a flourishing architectural activity. Unfortunately, from the four centuries immediately following the end of the Urartian kingdom, no architectural monuments have been uncovered in Armenia. It is only in the centuries just before the Christian era that our next link in the building tradition of the land is found.

Thousands of Armenian churches were built during the long history of Christianity. They varied in size from very small to large, though there were no giant structures like St. Peters in Rome or Hagia Sophia in Constantinople or the large cathedrals of Europe. Some churches were intended to stand alone, while others were parts of monasteries. A large number of types were developed, providing a great variety of exterior shapes and interior volumes. Some types are found in adjoining Christian areas, but in Armenia their plans were usually modified to conform to local conditions. A number of unique church forms were invented by Armenian architects in their pursuit of ever more efficiently built and aesthetically conceived houses of worship.

Armenian Carpet

The earliest remark about carpet weaving is found in the "Anabasis" by a 5th century B.C. Greek historian Xenophon. On his way back from Western Asia to Thrace Xenophon was invited by Seuthes to a feast. He wrote, "Timasion who had cups and barbarian carpets drunk to Seuthes and presented him with a silver cup and a carpet...". The fact that the 10000 Greek army retreated through the territory of the historical Armenia and that the historian mentioned barbarian carpets and not Greek "tapis" give us some grounds to suggest that the carpet given to Seuthes should have been Armenian.

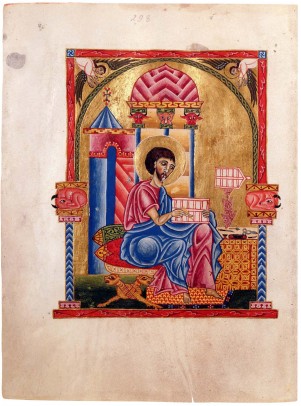

Decorative patterns and designs used in Armenian carpets were popular already in the early Christian period. They are best represented in the Armenian miniature art, as well as in the other areas of the Armenian applied arts such as architecture, sculpture, embroidery, cross-stones, wood and stone art, jewelry, national costumes and so on. Examples of such designs are the Armenian sign of eternity and the dragon sign.

Besides carpets various ancient carpet weaving tools and so called bone 'ktutich's (2-1st millennia B.C.) were found at the territory of historical Armenia. Archeological excavations discovered spindle heads (Shirakavan, Argishtikhinili), needles (Shirakavan, Noyemberyan), clay fragments with fabric patterns, a Bronze Age weaver machine and tools (Shirakavan, Lchashen, Argishtikhinili), a woolen clew (Karmir Blur). This was also cited by Assyrian sources (Ashurnasirpal of Assyria (9th century B.C.) and Sargon 2nd (8th century B.C.) mention captured fabrics and attires).Carpet loom is a device used to weave carpets, rugs, and cloth. The device to weave carpets (loom) is a big machine which is known to us from the 14th century lithographic sources. Until 70s of the 19th century a perpendicular wedge-shaped old loom was popular in Armenia.

Armenian carpets owed their high-quality also to the wool of ''Balbas'' sheep that were raised in the Armenian Highlands. Historical facts and various sources tell us about wool's unique quality and gloss. The Angora goat wool was widely popular in the Western Armenia. In the historical regions of Armenia where cotton and silk thread production was developed, both cotton and silk thread were also used in carpet weaving. In particular, cotton and silk were popular in the southern parts of Artsakh, Meghri and Nakhichevan; silk was used in Kharberd; and cotton – in the eastern regions of Vaspurakan and Ararat valley.

The red color of Armenian carpets was made from "vordan karmir" or "worm's red" dyestuff. The fact that "vordan karmir" dye was used in making of the oldest surviving carpet "Pazyryk" is a perfect example of this and has already been proven by the scientists in particular by I. Rudenko. "Pazyryk" dates back to the 5-4th centuries B.C. and can be seen nowadays at the Hermitage museum. Arab historians noted that Armenian carpets were the most valuable because they were made from high-quality wool and were dyed with durable "vordan karmir" pigment. This also explains why Armenian carpets were known in the Arab world as "kirmiz" (red).