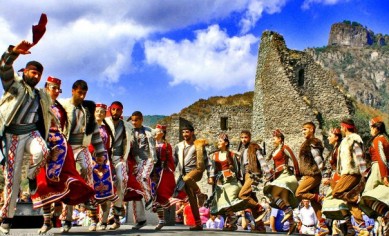

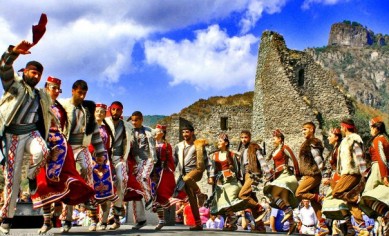

Armenian Dance Before 1915

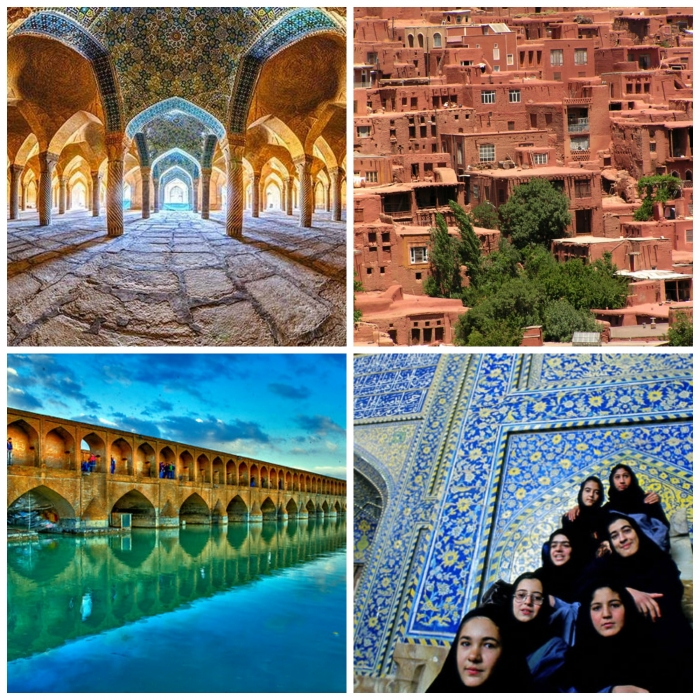

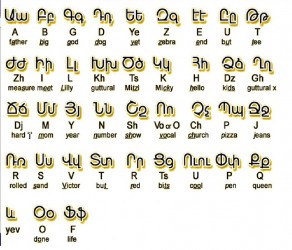

The Armenian dance heritage has been one of the oldest, richest, and most varied in the Near East. The ancestors of the Armenians established themselves in Hayastan (Armenia) about 650 Before Christ (B.C.) soon after the collapse of the Urartian Empire. The geographic position proved both a curse and a blessing. Located at a major crossroads between powerful empires, Armenia became a buffer state continually ravaged by invading armies, but distant enough to retain its own culture and identity.

The geographic location encouraged commerce and exposed the Armenians to many other peoples: Phrygians, Syrians, Persians, Hellenic Greeks, Romans, Laz, Jews, Byzantines, Arabs, Kurds, Seljuks Mongols, Osmanli, Georgians, Asiatic Albanians, Russians, and countless others. Armenian culture reflects many of these influences.

Although centuries of Ottoman subjugation changed or destroyed much of Armenia's "Great Tradition" (elite culture), the "little tradition" of the peasantry remained relatively unchanged for millennia. The rich dance heritage remained a living tradition into the 20th century. The Turkish massacres and deportations of 1,500,000 Armenians during world War I, and the subsequent dispersion of the survivors, irrevocably destroyed much of the dance heritage of Western Armenia, leaving scattered fragments of some dances. Many of these surviving fragments have since been lost due to modern cultural assimilation and urbanization.

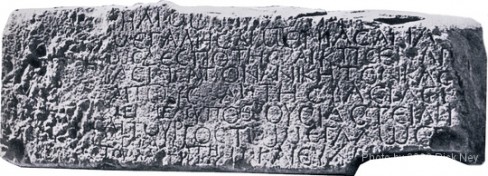

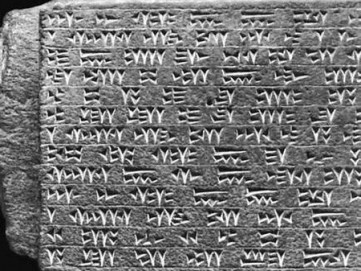

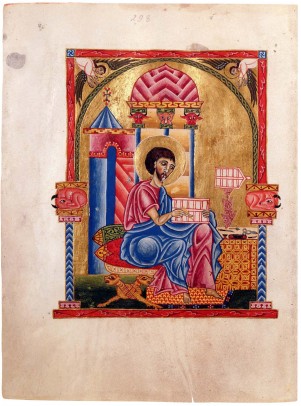

The destruction of most of the material culture has made it difficult to study the dance historically. Similarities in the poses found in Armenian dance with poses found in ancient Sumerian and Urartian artifacts have been cited as evidence of a direct relationship. These similarities do suggest the continuity of certain motifs but these motifs are also shared by neighboring ethnic groups. Most of the written records that have survived are ecclesiastically oriented (that is, illuminated manuscripts), and make little mention of the dance. These writers were clerics who viewed the dance as pagan in origin and generally ignored or suppressed it. The references that do exist indicate that many Armenian dances were originally totemic, imitating animals or nature.

Dance Types

The traditions of many centuries contributed to the development of the rich diversity in Armenian dance. The dance itself is divided into two categories: dances (barer), which were executed to the accompaniment of musical instruments, and song-dances (bari-yerker), which were performed to vocal accompaniment.

The traditions of many centuries contributed to the development of the rich diversity in Armenian dance. The dance itself is divided into two categories: dances (barer), which were executed to the accompaniment of musical instruments, and song-dances (bari-yerker), which were performed to vocal accompaniment.

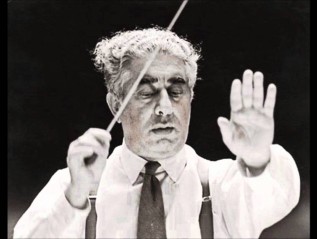

Dances were usually accompanied by musical instruments. In the village, the most common instruments were davul / tahul (a large drum), and zourna (primitive oboe). Other popular village instruments used were dudeksheeve and mey (shepherd's flutes), and daf (tambourine). The sax was a stringed instrument commonly played in Western Armenia, with the tar being its Eastern Armenian counterpart. The kemenche (fiddle) was used as a folk instrument on the Black Sea, but elsewhere was used to accompany the songs and poetry of the wandering ashoog (troubadour). A village ensemble often consisted of no more than two or three instruments.

In the cities, a more elaborate tradition of musical performance existed, with groups of musicians playing in orchestras. These musicians often played tar, oud, kanoon, snatur, nagar, kemenche, daf, dumbeg, and mandolin, or (starting in the 19th century) clarinet, piano, violin, and other European instruments. The music of urban ensembles was heavily influenced by urban "oriental" (Arabic, Persian, and Turkish) music.

These urban musicians considered Armenian village music to be "peasant' and "unsophisticated," and preferred playing Ottoman urban music (that is, longa, simai) and European music. The urban dances reflected this preference (that is, chifte-telli, waltz, quadrille). It was essential for a rural or urban band to have a good singer or skilled joke-teller, who could create impromptu lyrics. Improvisation was an intrinsic part of Armenian culture.

Some of these songs were ancient but many were improvised ditties reflecting the issues of the day (that is, the local gossip), and changed frequently. The lyrics themselves were not only in Armenian but also in Kurdish, Turkish, Azerbaijani, Greek, etcetera. In many areas of Armenia, these other languages were commonly used by Armenians, often in addition to their own Armenian language. Armenians often composed songs in these other languages or adopted songs created by these neighboring ethnic groups.

Armenian dance has a wide variety of formations. The dances are often performed in an open circle, with the little fingers interlocked. In general, the dances moved to the right (counter-clockwise), although there are a few areas that moved clockwise to the left (that is, Yerzinga). The basic structure of the dance could be either men only, women only, or mixed lines. The number of dancers also varied: group/line/circle dances, solo dances, or couple dances. In rural Western Armenia, the couple dances were commonly done by members of the same sex (that is, Women's duet from Chamokhlu, men's combat dances). A man and woman dancing together as a couple was more typical of the urban areas, or Eastern Armenia.

Armenian dance could also be broken down into two distinct styles of dance, "Western Armenian" (Anatolian), and "Eastern Armenian" (Caucasian). These two major styles are also subdivided into regional styles (that is, Van, Lori). Eastern Armenian, the style of the Transcaucasus Mountains, displays ballet-like movements and acrobatics in its oirginal folk form, particularly the men's dances. This is the style usually performed by most Armenian dance groups today, who are influenced by the repertoire of the State Dance Ensemble of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (S.S.R.).

The Role Of Dance

The modern concept of a dance/party (hantess/kef), as a distinct social function with a band playing, etcetera, is an Armenian-American innovation, and did not exist traditionally. A party was not a separate function in itself, but merely one aspect of some major event or festivity which included the entire community (that is, a wedding). There were European balls in the cities for the urban Armenian merchant classes, but these had little in common with the village festivals. A poor villager did not have a band conveniently playing when he wanted to dance, nor did he need one, for he could provide his own music by singing a dance-song. The traditional village dances varied widely and encompassed all aspects of village life. The dance was not simply and idle amusement, but and organic part of the culture. Any event, such as an engagement, would include special music, songs, and dance.

A dance often combined several functions simultaneously. The following description illustrates the multiple roles. It describes Armenian pilgrims dancing at an Ascension Day festival in the Armenian monastery on the outskirts of Treibizond. International folk dancers familiar with Pontic Greek dancing or Turkish Black Sea dancing will recognize this as the Armenian cognate form.

Continuity and Change

Armenia had a multiplicity of distinctive regional subcultures, many of which had their own characteristic dialects and customs, including dances. The extensive mountain ranges isolated villages and encouraged variety. The Armenian peasantry was noted for its improvisational skill in songs and dances, often creating new songs and dances to commemorate particular occasions and noteworthy local events (that is, Papertzi Gossip Dance). As time passed these topical songs would be forgotten, as new events inspired new songs and dances.

The same geographic isolation that encouraged diversity also maintained continuity in the music and dance tradition within each area because a creative villager would draw upon his traditional elements as his artistic source. Thus, a new village dance would closely resemble the old dances, maintaining the artistic continuity, because they both used common traditional elements of that particular community. Although the regional style would change, as do all living traditions, it would do so very slowly over many generations.

Armenian villagers did travel, particularly as pilgrims to the large religious festivals. There they would be exposed to the music, songs, and dances of other villages and regions. When they returned home, they would describe and demonstrate these for their own village, often adding a local flourish to the song or dance. Some of these might be incorporated into the local repertoire, and modified to suit local tastes.

Another major factor in the diffusion of dance was the large scale transfer of populations to other areas. Life in Armenia was precarious due to its geographic and political position. Foreign invaders forced large segments of the population to move, at several points in history. Seljuk invasions in the 11th century led to the Armenian settlements in Sepastia and Cilicia. In the 16th century Shah Abbas deported a large number of the Armenian population to Persia. Nomadic Kurds then migrated into depopulated Western Armenia, which they presently dominate.

As a result, Armenian song and dance did not exist in discrete isolated units. Instead, it resembled an Oriental tapestry, combining different elements. Although the regional style of music and dance remained intact, some of the songs and dances may have originated elsewhere in a different form, and have been assimilated locally. Many songs were widespread, with different dances accompanying them in different areas (that is, Hoy Nar, Lepo Le Le). Conversely, the dance could be widespread, and done to different songs in different areas (that is, Bar, Sword Dance).

The variety of Armenian dances as so extensive, and documentation so poor, that few individuals are familiar with even a fraction of the dances. A brief list of regional dances could include:

Sepastia–ChekeenHalay, Bijo, Jan Perdeh, Divrigtsi Bar, Govduntsi Bar, UchAyak/Sepastia Bar, Preperttsi Bar.

Erzerum–KhoshBilezig, Kher Pan, Berzanig, Shavallee, AkhaltzikhaVart, Dasnachoors, MaroYerekVodkh.

Van–Lepo Le Le, Govand, Daldalar, Papuri, Lorge, Sinjani, Sulimani, Sherokee, HaireMamougeh.

Daron–Yarkhoshda, Tooran Bar, Shoror, Gorani, Lorge, KotchariLatchi, Bingeol.

Urmia–Janiman, Sinjani, BandiShalakho, TachayalKitchari, Sheikhani, RoostamBahzee.